THE NORTH WALES COAST RAILWAY: HISTORY

Rheilffordd arfordir gogledd Cymru

Crewe to Holyhead

In 1801, the British Government passed an Act of Union, and all Ireland became integrated with the United Kingdom, with its own members elected to the London Parliament. The only communication link between London and Ireland was by horse-drawn road coach and sailing ship; the shortest sea link to Dublin being between Holyhead and Kingstown (now Dun Laoghaire). One of the first of the great British engineers, Thomas Telford, was employed to improve the Holyhead road, later called the A5, and created the suspension bridge at Conwy (now cared for by the National Trust) and the high bridge over the Menai Strait to the island of Anglesey. North Wales is a mountainous area, but Telford brought his route from London on a direct route through Llangollen and Bettws-y-Coed.

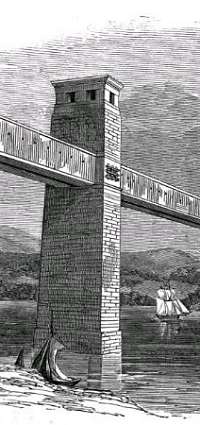

The invention of railways led to demands for a rail route to Holyhead, and the great George Stephenson, predicting that fast and heavy trains would need to use the line, proposed a northern route which avoided the mountain passes by running along the coast from Chester. The Chester and Holyhead Railway Act was passed in 1844, and construction began on 1 March 1845 with George's son Robert Stephenson as chief engineer. (The Chester and Crewe line was built by a separate company, and opened in 1840.) Even though the route was largely along the coast, some bold engineering was needed, especially the high bridge across the Menai Strait (required by the Government to give clearance for shipping). The Irish Mail went to Holyhead by train for the first time on August 1 1848, and on the same day the present Chester station was opened, replacing the separate stations previously used by Crewe and Birkenhead services.

Small companies such as the Chester and Holyhead rarely

kept their independence, and in 1859 the north Wales coast

line had become the property of the London and North

Western Railway Company (LNWR) which had in fact been

working the train services from the opening day. The LNWR,

which owned the west coast main line from London Euston to

Carlisle, set out to promote traffic on the coast line by

encouraging tourist traffic to the seaside resorts,

notable Rhyl, Colwyn Bay, and Llandudno which was reached

by a short branch line opened in 1858. Many sections of

the line were expanded to four tracks, and larger stations

built to handle the traffic; level crossings were replaced

by road bridges, as can clearly be seen today near Rhyl

and Prestatyn stations.

Manchester to Chester

Trains from Manchester Piccadilly to North Wales normally

reach Chester via Warrington Bank Quay. The line from

Ordsall Lane (on the outskirts of Manchester) to

Earlestown is particularly historic as it is part of the

Liverpool and Manchester Railway, opened in 1830 as the

first inter-city railway in Britain, if not the world. At

Earlestown, trains turn south to join the metals of the

Grand Junction Railway, which opened soon afterwards, in

1833, giving Liverpool and Manchester a link to

Birmingham.

The Twentieth Century

After World War I, many of the railway companies were in a poor state, and an Act passed in 1921 merged them into larger groups, with effect from 1923. The coast line thus became part of the London, Midland and Scottish Railway company, which ran it with few changes or improvements through the depression years and the Second World War until 1948, when the post-war Socialist Government took over all the railways, by now very run-down, and merged them into British Railways, renamed British Rail in the 1960s. The post-war years saw the introduction of paid holidays for the majority of workers, which in turn led to booming summer traffic as people took their holidays in the resort towns. Operationally, however, little had changed since 1923 except that the locomotives became somewhat larger. Steam locomotives, increasingly neglected in appearance and maintained at a large number of labour-intensive depots, reigned supreme on long-distance trains until the early 1960s, although diesel railcars had appeared on local trains soon after the publication of the 'British Railways Modernisation Plan' of 1955. This era is seen by many who were young at the time as a golden age: the reality, however, was one of slow, crowded dirty, and not always frequent services.

No sooner had the diesel locos begun to turn the coast

line into a modern railway, the Conservative Government

appointed a manager from the chemical industry called

Richard Beeching to try to transform the railways into a

profit-making concern. To Dr Beeching and his advisors,

this meant concentrating on profitable traffic, to the

exclusion of any lines and stations seen to be

loss-making. Many coast line stations were listed for

complete closure: there would have been no stations in the

30 miles between Chester and Rhyl if the plan had been

carried out in full. The plan was modified following many

objections, but a number of stations still closed in the

1960s, as Beeching seemed to have no understanding of the

idea of unstaffed stations with conductors on the train.

Most branch lines lost their tracks, leaving just the

Llandudno and Blaenau Ffestiniog branches open to

passenger traffic. Later regimes were more sympathetic,

and with support from local authorities some stations

later reopened: Shotton, Llanfair PG, Valley and most

recently (1987) Conwy.

Modern Era

The last BR mainline steam train ran in 1968, and the

coast line settled down to a diet of diesel-hauled

expresses and diesel railcar locals. Seasonal resort

traffic fell away as car ownership and foreign holidays

increased, but traffic to and from Ireland remained a

major source of income. Class 40 diesels, built by English

Electric and an older and larger brother of the Class 37s,

were the mainstay on major trains for many years until

they were withdrawn as life-expired in the early 80s, but

Classes 45 and 47 were also seen as well as some of the

smaller diesels of classes 24 and 25. The four-track

sections of the line gradually reverted to double track.

The next upheavals, however, came as a result of the decision to divide British Rail into 'business sectors' in the mid 80s. Most trains on the coast line fell into the province of the Provincial Sector, later renamed Regional Railways, which was forced to make huge economies in order to make a case for new trains which materialised as the Class 150 'Sprinters' and the bus-based Class 142 'Pacers.' For a period, discomfort and overcrowding reigned: it became common to see Class 142s, comprising two four-wheeled coaches with low-backed seats, on services between Holyhead and Hull or Scarborough on the east coast of England. Meanwhile, a new dual-carriageway road called the North Wales Expressway was being blasted along the coast, creating an infernal noise at many lineside locations and stealing even more passenger traffic. Freight was abandoned almost completely, including all the container trains to Holyhead, and even the locomotive fuel to Holyhead depot, leaving just a handful of weekly trains carrying specialist materials.

Fortunately, as the 90s dawned and the Government began

to think of privatising the railways, the management of

Regional Railways North West, later renamed North West

Regional Railways. saw a solution to the coast line's

problems in the shape of Class 37 diesels displaced by

railcars in the Scottish Highlands, and coaches from,

among others, the London Waterloo - Exeter route which had

been modernised using new railcars originally intended for

use on the coast line. The political reasons for this

remain obscure, but it certainly provided more seats than

would otherwise have been available as well as a treat for

'real train' enthusiasts. The Class 37s appeared

gradually, until by 1995 a basically hourly service

between Crewe and Bangor was running, with some trains

extended to Holyhead. Another 1990s development was the

introduction of 'InterCity 125' trains on the London

services which were operated by the Inter City sector,

largely displacing Class 47s, although the 47s returned a

few years later for a final farewell.

In 1994, a new organisation called Railtrack came into

being, taking over ownership of all British Rail's land,

track and signalling. All the shares of Railtrack were

sold on the open market during 1996, as a wholly private

company responsible for all signalling as well as track

laying and maintenance, so all signalling staff were

Railtrack employees. However, it was not to last. In 2002,

it ran into financial difficulties, and was closed down by

the Government, replaced by a state-owned body called

Network Rail.

Also in 1996, the majority of freight locomotives and

wagons in Britain were sold to a consortium led by the

Wisconsin Central Railway, and formed into a company

called English, Welsh and Scottish Railway which owned all

the Class 37/4 locos used on the coast line. Most

passenger equipment was sold to new 'leasing companies',

and finally the operation of the passenger trains

themselves was 'franchised' to what are called Train

Operating Companies.' North West Regional Railways

operations were taken over in 1997 by a new company called

North Western Trains, and the London services passed to

Richard Branson's Virgin Group.

Into the 21st century

By 1998, both had fallen under the spell of large groups

from the bus industry; 49% of Virgin Trains ws in

the hands of the Stagecoach Group, whilst North Western

Trains was taken over by FirstGroup and was known as First

North Western. Towards the end of the seven-year franchise

for the local services, it was decided by the Strategic

Rail Authority to re-arrange the franchise map and create

a new 'Wales and Borders' company which would operate all

the non-inter-city services in the area. North Wales

services spent a few months being run by a subsidiary of

the National Express group, before the whole passed to the

Arriva company to become Arriva Trains Wales from the end

of 2003. When the franchise came up for renewal from 2018,

under the auspices of the Welsh Government, it was decided

to use a brand name which would be independent of the

operating company, and new franchise holder KeolisAmey

uses the brand 'Transport for Wales.' In 2020 the

company was nationalised by the Welsh Government,

retaining the same name.

Virgin Trains ceased to exist in December 2019, having

lost the franchise, and a new company, Avanti West Coast-

a joint operation by First Group and the Italian National

Railway took over the London services.

New passenger trains arrived in North Wales at the start

of the 21st Century, basically diesel railcars although

perhaps more luxurious than those in use previously.

Locomotive haulage of the traditional kind ended in 2006,

although from 2008 a Monday - Friday Holyhead - Cardiff

and return working has been hauled by a locomotive,

subsidised by the Welsh Assembly Government. An unusual

version occurred for a while in the 1990s and early 2000s,

as Virgin's 'Pendolino' electric trains on London services

were towed by locomotives along the non-electrified line

between Crewe and Holyhead.

By 2010 the only freight trains to be seen on the Coast

line west of Chester were (very) occasional stone trains

serving Penmaenmawr quarry and the short 'flask' trains to

Valley which service the power station at Wylfa. The power

station ceased generating, but trains continued to

run to return the fuel elements to Sellafield until late

2019 when the de-fuelling was completed. By 2021

there were some signs of a freight revival, however.

Updated by Charlie Hulme November 2023

To the

North Wales Coast main page